Where is the rest of my body?

Colonial continuities of constructed

narratives in the appearance of

consumed buddha heads.

Schirin Al-Madani & Bon Kim

Within the framework of the residency in Circa 106, we

began the search of addressing colonial constructs in the

consumption of design objects that touch on issues of

cultural appropriation, othering, the perpetuation of global

hierarchies and mass consumption, to name only a few.

Download text as pdf

The objects purchased for this exhibition will be returned to their sellers at the

end of the open studios, so as not to participate in the cycle of re-producing a

suppressive pattern of consumption and rewriting the narrative of those made

into 'others'.

Thank you for engaging with our thematic quest by being here.

Introduction

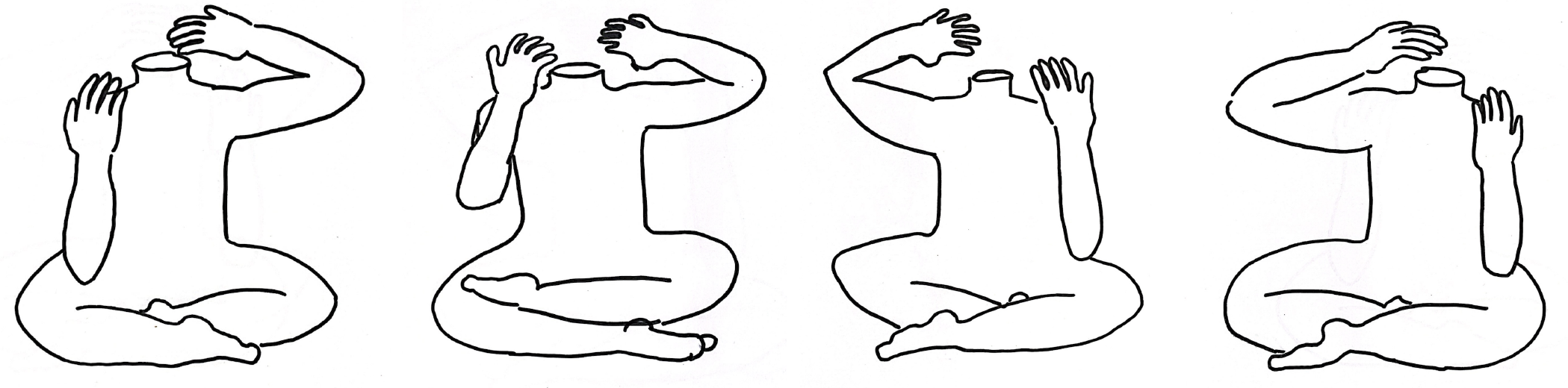

Through our work, we want to approach an analysis of colonial continuities by tackling it through the emergence of the consumption of buddha heads 1 in Western societies. The heads that get produced for art decor purposes, enable the viewer to decode societal power relations and colonial continuities on closer observation. In our investigation, we ask questions about the absurdity of the disembodied head, which has become an object, transferred to a Western environment - then given a supposed new meaning by Western regimes. By reconstructing the disconnected historical link in the act of consuming the head of Buddha, by addressing the act of violence in a cutted head, one can dismantle hegemonic systems through observing it, raising critical questions about cultural appropriation of objects and practices - in this case: mass consumption of sacred artefacts - that have been forcibly removed from their context and corporeality.

We question how buddha heads are consumed - without a connection to colonial history, and instead bought en masse as artificial home decoration objects. This discrepancy raises unresolved matters that need to be addressed critically in terms of historical connection and a re-examination of colonial heritage; further as a representation of Western dominance of consumption and as a global pattern of structural subordination of non-Western traditions and practices. We therefore ask:

Why are buddha heads produced as art decor objects and consumed like crazy in the West? What is the historical and the contemporary construction of a Buddha as well as a foreign appropriation in the West and what therefore means owning it through a Western gaze? Why is it the head and not the whole statue that gets consumed especially? Why did the head need to be cut off, to be consumed by Westerners? 2 Why was this particular head taken to the West and why do people have to take it into their homes? What is it supposed to bring to them? Further, why is there a lack of awareness to understand the consumption of a severed head?

These questions no longer seem to be present or relevant in consumption, rather they may have been submerged into a normalised Western concept of consumerism. Colonial violence is anchored in historically established global systems and only becomes visible when it is explicitly decoded and understood as constructed norms of hierarchies. The reproduction of neo-colonial economies, which maintain themselves through chains of commodities, enriched by what brings profit, cannot be evaluated and analysed without considering their time of establishment. What sells well today was and therefore gets now widely consumed as something ‘to have’, maybe something supposedly 'exotic' or ‘unique’? In a structured world that seems to maintain hierarchies at all costs, consumption does not stop at the heads of religious deities, practices, traditions or people. The neo-colonial world shapes appropriated traditions and practices as it suits its own cycles of selling and buying. We therefore want to dare the attempt to allow questions about the emergence and origin of the consumption of buddha heads with our exhibition and thus illuminate a section of structural dynamics, which for us are connected to the colonial past, but which hardly seem to be reflected upon.

2 In some cases, the head is open, evoking the vision of a cut brain of a sacred statue?

Our own positioning and perspective

The thematic exploration of colonial entities in Western societies emerged from

our work exchange. Based on our initial ideas, which brought us together in Circa

106, we developed within our dialogues, in which we searched for colonial

visibilities in societies, an idea to initiate a critical conversation about the (mass-)

consumption of imported, appropriated artefacts, their (de-)construction and their

connection to colonial pasts. We would like to invite you to deal with these topics

in relation to social trigger points and structures, as well as their history of origin,

and encourage you to question the seemingly self-evident characteristics of

manifested conditions. We understand our work as a starting point to look from

here into the past and to consider who dominated it, who constructed it, which

appropriation practices are continued unquestioned and with which

consequences that seem invisible - to be able to then draw a connection to

‘today’, an explanatory approach for immanent problematics and trigger points of

social structures and to consider how a decolonial approach could be imagined in

the future.

Where is the rest of my body? - looks at Western consumption of the buddha

heads as a case study of colonial continuity that has connected our questions

about origins and syntax. We are less focused on a view of religious relations of

appropriation and dominance - and more on decoding an absurdity in

consumerism that has become seemingly subtle, even unrecognizable for

Westerners, and in buying the heads and displaying them very normalized. In

order not to participate in this dynamic, we will return the heads acquired for the

exhibition after the exhibition.

When considering our questions, it is necessary to describe our own positioning

from which we look at the investigation: Our ancestors have both been

historically affected by colonization, which is not insignificant for our reflections,

since our own emotionality can resonate in this context. At the same time, it

allows us, as artists and scientists, to look at social phenomena and to question it

from our own perspective. Therefore, please feel invited to expand our questions

from your own horizon. So following we will start the thread of dialog inviting you

to join us:

How do you (de-)construct?

How are buddha heads consumed and therefore (de-)constructed as well as

appropriated in the West? In order to get to the bottom of this question, it is

necessary to draw a historic connection, which is marked by influences of

colonial history. However, within the observation it becomes questionable who

(re-)constructs the past in which way, from which perspective, and how. “A

growing number of critical historians argue that historical narratives are made, not

found; that they reflect discrete events pieced together into a plot that the

historian crafts and then interprets for its overall significance as a story (...)”.

(White 1987; Jenkins 1991). It is thus questionable how the Idea of the

consumption of Western societies came to the choice of buddha heads and how

their stories have been interpreted in a so-called ‘modern world’. 3 Furthermore,

why particularly the heads are consumed as design objects and - in this

exemplary view - often decorate Western living rooms without an entire body? In

addition, it is necessary to understand what kind of appropriation mechanisms,

what forms of appropriation the heads re-produce through their consumption in

the West? Furthermore, it is interesting to take a look at feedback effects that

become visible as a result of this. At the same time, we have to take into account

that by offering the heads for purchase and ‘designing’ Western homes, the

narrative about an engineered history and about so (re-)constructed ‘others’ is

influenced and rewritten, or even forgotten - which brings us to the original

problem - the question of who (re-)constructs whom and why?

In order to find a proximity to these questions, we need to understand how

Western constructions about imagined 'others' have emerged and in which form a

dynamic of consumption is related to an imagined ‘otherness’ today, or why it is

problematic to maintain such dynamics of ideas. The Western constitution of an

imaginary 'other'4 is a concept that Edward Said decoded with his

discourse-initiating text ‘Orientalism’ which gave rise to the postcolonial 5

discourse. The Western concept of the ‘other’, which was used as a discursive rhetoric of demarcation, marked the basis of legitimisation for colonial use of

violence in order to suppress those made into ‘others’. Through the constructed

discourse 6 of what was defined as ‘the other’ (in his example the imagined

‘Orient’), the West was able to set a superiority over an imagined ‘rest of the

world’, which ordered people into hierarchies, while elevating the West above

those defined as 'other'. 7 This dynamic, deciphered by Said, must also be

considered when looking at the historical development of Western consumption

in general and specifically on the consumption of buddha heads, as well as the

means of cultural appropriation. 8 It also shows why cultural appropriation could

be viewed critically. “The wrong of cultural appropriation is rooted in imbalances

of power. Whether a particular case is most saliently understood as one of

silencing, exploitation, misrepresentation, or offense, what ultimately makes

particular instances of cultural appropriation wrongful, and thus what grounds

objections to them, is the way in which they manifest and/or exacerbate

inequality and marginalization. Call this the oppression account of cultural

appropriation.” (Matthes 2018: 1003). We consider that appropriative practices as

well as the consumption of 'other' religious objects or practices can also be found

in relation to an appropriation on the one hand, but also a shaping of narration

and discourse of Buddhist practices:

As Berkwitz argues “(...) it was largely emissaries and Orientalist scholars from

Europe who decided that geographically and culturally diverse communities of

people who worshiped the Buddha were all members of a single religious

tradition called Buddhism, bouddhisme, or Buddhismus. In the nineteenth

century, Buddhism was first rendered into a discrete entity that exists, albeit in a

variety of forms, (...) open to the gaze of Western travelers, scholars, and

missionaries, before later being reinvented as an object of knowledge to be found

in the texts and manuscripts housed in institutes in Europe.” (Berkwitz 2006: 3).

As already mentioned, supposed knowledge was produced in a way that

manifested itself through public discourse. The effective use of discourse serves

to construct realities that, according to Foucault, do not necessarily have to

correspond to the truth, but are rather an output of power relations. Accordingly,

"(...) there (is) a struggle for truth (...). (Truth is to be understood as) the

ensemble of rules according to which the truth is endowed with specific effects of

power, (...) (it is) about a struggle for the status of truth and for its economic and political role. One must not approach the political problems of intellectuals in the

categories of 'science/ideology', but in the categories of 'truth/power'." (Foucault

1978: 53 in Jäger and Jäger 2007: 1). The hierarchy thus established, positioning

the West above the imagined ‘other’, not only established the European idea of

'the West and the rest'; it created a Western norm against which the rest of the

world,9 i.e. people, actions, traditions, value and belief systems, materialities,

objects, institutions and educational systems, etc., were measured. 10 “In this

sense, historical surveys of (...) subject can never be transparent accounts of the

way things “really happened” because, in part, the events written about are

selectively chosen and arranged into a linear narrative that deviates from the

often haphazard, unconnected manner in which they occurred as discrete events

in the past.” (Berkwitz 2006: 2).

To us the immanent continuity inherent in a construction of an 'other' becomes

clear in the consumption example of buddha heads in the West. A continuity of

colonial dynamics of Western modes of thought and agency can unfold, because

consumption seems to go only in one direction when looking at the consumption

of heads. It then becomes questionable to what extent the heads are bought in

their 'former' (whatever that might be) environment and, if so, what this can mean

in relation to power dynamics. Nevertheless, a historically imagined and

manifested cult of consumed buddha heads can be observed as problematic. On

the one hand, because in this way sovereignty over an owned narrative is

undermined; furthermore, the reconstructed image of cutting off a head of a

sacred object is problematic within modes of consumerism, because it

perpetuates the brutality of colonially constructed dynamics of domination. On the

other hand, consume seems so normal, so unquestioningly progressing that the

head's inherent history seems to remain unreflected. We therefore aim to start

decoding the perfidious ideas of interpretations, by criticising the mass production

and consumption of the heads as appropriated object, but also in showing how

an idea of superiority over a non-eurocentric world is shaping Europeans into

habits of unconscious consumptive behaviors and cultural appropriation without

untying a colonial heritage that is carried into these home decor objects.

4“(...) ‘Othering’ is defined as a process in which, through discursive practices, different subjects are formed, hegemonic subjects - that is, subjects in powerful social positions as well as those subjugated to these powerful conditions.” (Thomas-Olalde und Velho 2011: 27).

5 A Definition of ‘postcolonialism’ is in this context understood as by Ashcroft, Griffiths and Tiffin: “We use the term ‘postcolonial’, however, to cover all the culture affected by the imperial process from the moment of colonization to the present day.” (Ashcroft, Griffiths & Tiffin 2002: 2).

6 In the sense of a Foucauldian understanding, discourse is understood here as “(...) a reality-constructing framework (...)”. (cf. Jäger and Jäger 2007: 19).

7 "In a quite constant way, Orientalism depends for its strategy on this flexible positional superiority, which puts the Westerner in a whole series of possible relationships with the Orient without ever losing him the relative upper hand." (Said 1995: 7).

8 “Cultural appropriation refers to the handling of things from "non-cultural" contexts. The model includes culturally specific forms of acquiring, "using", reworking, consuming, and the changes in meaning associated with all these processes.” (Schreiber 2013: 48). (Translated from the original: “Kulturelle Aneignung (cultural appropriation) bezeichnet den Umgang mit Dingen aus „kulturfremden“ Kontexten. Das Modell beinhaltet kulturspezifische Formen des Erwerbs, des „Einbrauchens“, des Umarbeitens, des Konsumierens und den mit all diesen Vorgängen verbundenen Bedeutungsänderungen. Ich werde analysieren, ob, in welcher Weise und mit welchen Einschränkungen dieses Modell gewinnbringend in die Erforschung der Vergangenheit eingebracht werden kann.” (Schreiber 2013: 48)).

9 "By 'discourse' we mean a particular way of representing 'the West', 'the Rest' and the relations between them." (Hall in Das Gupta et al. 2018: 86). Since then, the West has represented the discursive 'one' as the norm against which the 'rest', the 'deviants', have to measure and orient themselves.

10 “Everyone who writes about the Orient must locate himself vis-á-vis the Orient; translated into his text, this location includes the kind of narrative voice he adopts, the type of structure he builds, the kind of images, themes, motifs that circulate in his text - all of which add up to deliberate ways of addressing the reader, containing the Orient, and finally, representing it or speaking in it’s behalf.” (Said 1995: 20). This concept is further articulated by Gayatri Spivak in her work 'Can the Subaltern speak? from 1988' (cf. Spivak 2015: 152). The discourse is thus about the reproduction of power over the 'Other'; and about the naming of the 'Other' from a Western perspective as a discursive exercise of power through the supposed production of knowledge about 'them'.

Why do you consume?

The question to be asked thus remains: why the consumption of buddha heads

seems to progress? What seems to be the attracting element here? Hence, why

even in the form of a decapitated body? Where does the Idea of consuming

buddha heads arise, next to a tied history of cultural appropriation and a

constructed superiority - as referred to above? Therefore the second fundamental

question we need to ask ourselves in considering our example is what might be

the agency in consuming, hence what purpose does the consumption serve? In

addition, it becomes debatable what is meant by a de-corporalization in the

sense of a separation of head and body in itself and in objects. This generated a

more subjective encounter with the headless body, which led to questions such

as: Why do you consume? or: What does it mean to be headcutted and

consumed?

We understand our work as a stimulus to give thought to these questions, which

we are trying to address with a critical view. Mass consumption of artefacts and

their socio-political contexts as well as (re-)writing seem to raise many thoughts

that we, as the observers, need to reflect upon our own conditioning and

perspective we look at the phenomenon from.

It would be foolish not to acknowledge that we are equally influenced by

structural consumption and cannot escape societal constructions, even if we do

not have budda heads at home and tend to be provoked to think about them and

question their very existence. But we are as well influenced by power relations

that 'globalization' perpetuates. 11

As a result of globalization and economic markets as well as trading cultural

forms and objects (see Svašek et al.), “(...) a per- son’s livelihood (...) becomes

unfixed and uncertain. This condition has been described in terms of an

increased reflexivity, wherein all forms of knowledge about oneself and the world

are constantly subject to revision in the face of new ideas and opportunities to

act. This disruptive effect of globalization has contributed to distinctively modern

reworkings of what it means to be Buddhist and how one can model and develop

this identity in practice.” (Berkwitz 2006: 7).

Asad identifies secularity as the second critical feature in steps made to advance

the ‘project of modernity’ (Asad 2003: 16). For him, secularity relates to a wide

plurality of concepts, practices, and sensibilities that collectively maintain the

freedom and responsibility of one' s sovereign self vis-à-vis religious discourses

or practices, and that attempt to constrain it in various ways. Berkwitz calls this further the ‘privatization of religion’ and says that: “(...)its exile from the public to

the private realms of people’s lives, has allowed other powers such as the

modern nation-state, capitalist economies, and military institutions to exert more

control over the public aspects of human societies. Secular powers, including

those advanced by globalization, obtain a greater ability to effect the ordering of

societies when a generalizable system of ethics is disjoined from religion and

justified in terms of its pragmatic benefits for the public as a whole. Serving as the

counterpart of religion, the secular works to confine religion to the private sphere

and offers alternative rationales for managing social interactions between

people.” (Berkwitz 2006: 7). From this, individual ideas may be derived that

shape and ultimately (re)construct the narrative of buddha heads, as described

above. This is where it would be very interesting to explore a more in-depth

analysis of their narrative. It would be necessary to use quantitative and

qualitative methods in order to get a picture of the actual idea about the buddha

heads given by their consumers and to find out what story they feed to the heads

and what is meant by this. Ultimately, it can be stated that colonially established

structures and hierarchies dictate the demand and production of plastic (and

other materials) 12 buddha heads in accordance with their demand as well as in

terms of a 'form' dictated by consumption. For us, it was exciting to connect

colonial history with contemporary consumption practices and thus look at

another fragment of colonial traces. 13 “Indeed, the life story of the Buddha is

paradigmatic for most communities and a opular resource for all sorts of textual

and iconic constructions.” (Berkwitz 2006: 3).

12 E.g. ceramics, wood, mixed materials and similar ones.

13 "The great attraction that (...) emanates from postcolonialism is due to the enrichment that characterizes every actual paradigm shift". (Albrecht 2008: o.p.). As noted, the prevalent postcolonial discourse makes it necessary to question and re-evaluate the production of knowledge in colonial discourses, colonial language and colonially manifested ways of thinking, and thus to advance the process of decolonisation, which calls for a rethinking and thus strives for more non-violent social structures, because colonialism can only be implemented with brutal violence. A radiation of postcolonial rethinking is thus necessary in all areas of social life, which makes a reflection of language, actions, hierarchies - ultimately of the architecture of our society - necessary.

(Not a) Conclusion

The present is shaped by the colonial past. The consumption of imported

practices and objects is directly related to neocolonialist economic systems. The

consumption of buddha heads can therefore not be viewed uncritically or

unseparated from the colonial past. Questions that arise can be reconstructed

linearly and retrospectively on the basis of history and on the basis of established

economic systems - but the collective forgetting and especially silence about

colonial acts of violence blur the responsibility of a historical examination of

colonial history and make a de-melting of colonial manifestations from

established systems, such as religious practices, economy, consumption,

language, education, normativity, etc., impossible. This observation is not new,

but it seems that every friction that is recognised, and which stands out from the

identification of colonial outputs, gives rise to a social or political response of

oppression. In other words, colonial structures are so immense in their infiltration

of global systems that they no longer seem visible and their emergence is neither

remembered nor questioned. It is seen as something normal. But it forgets that a

beheading separates a head from its body. What is needed, therefore, is an

acknowledgement of the structures of violence that can still be seen today when

we begin to decode systems and understand the archaeology of knowledge and

the systems that have been constructed. Colonialism demands violence and

death. It denies accepting the world as it is and shaping it into what it should be

to serve the hierarchies. Hence, the world is structured according to the needs of

capitalism, which perpetuates the circulation of violent acts.

With the consumption of buddha heads, consumers may no longer be aware that

what they are expressing with their consumption as an act is a form of violence.

This is precisely the problem that this exhibition aims to address.

1. Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

2. Ashcroft, Bill, Griffiths, Gareth, and Tiffin, Helen (eds) (1995): The Post-colonial Studies Reader, London: Routledge.

3. Bayly, Christopher A. (2006): Die Geburt der modernen Welt. Eine Globalgeschichte 1780-1940. Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag.

4. Berkwitz, Steven C. (2006): The history of Buddhism in retrospect. In: Buddhism in World Cultures. Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara/California/Denver/Colorado/Oxford: ABC Clio.

5. de Jong, J. W. (1976): A Brief History of Buddhist Studies in Europe and America. In: ‘The Eastern Buddhist’ Vol. VII, 1974 / First Indian Edition, 1976.

6. Foucault (1972): The Archeology of Knowledge. London and New York: Routledge.

7. Foucault, Michel (1977): Die Ordnung des Diskurses. Frankfurt a.M.: Ullstein.

8. Gaub, Daniella: Westliche Identitätsbildung durch den kolonial und diskursiv konstruierten Kulturkonflikt. Online abrufbar, unter: https://www.academia.edu/28747910/Westliche_Identit%C3%A4tsbildung_durch_de n_kolonial_und_diskursiv_konstruierten_Kulturkonflikt (Last visit: 29.04.2022).

9. Hall, Stuart (2018): The West and The Rest: Discourse and Power. In: Das Gupta, Tania; James, Carl E.; Andersen, Chris; Galabuzi, Grace-Edward; Maaka, Roger C.A.: Race and Racialization. Essential Reading. Second Edition. Toronto, Vancouver: Canadian Scholars.

10. Jäger, Margarete; Jäger, Siegfried (2007): Deutungskämpfe. Theorie und Praxis Kritischer Diskursanalyse [Fighting About Meaning. Theory and Practice of Critical Discourse Analysis]. Nürnberg: Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung.

11. Jenkins, Keith. 1991. Re-thinking History. London: Routledge Press.

12. King, Richard (1999): Orientalism and Religion. Postcolonial theory, India and ‘the mystic East’. London/New York: R Taylor & Francis Group.

13. Matthes, Erich Hatala (2018): Cultural appropriation and oppression. In: Philos Stud (2019) 176: Springer Nature B.V. pp. 1003–1013.

14. Mignolo, Walter (2000): Local Histories/Global Designs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

15. Nehring (2012): Postkoloniale Aneignung. De Gruyter.

16. Prebish, Charles S. (2002): Studying the Spread and Histories of Buddhism in the West. The Emergence of Western Buddhism as a New Subdiscipline within Buddhist Studies. In: Buddhism beyond Asia. University of California Press.

17. Said, Edward W. (1995): Orientalism. Western Conceptions Of The Orient. Third reprint. London: Penguin Books.

18. Schreiber, Stefan (2013): Archäologie der Aneignung. Zum Umgang mit Dingen aus kulturfremden Kontexten. Exzellenzcluster TOPOI, Freie Universität Berlin.Forum Kritische Archäologie 2, 2013, pp. 48-123.

19. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (2015): Marxistisch-feministische Dekonstruktion: Postkoloniale Theorie: Eine kritische Einführung, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2015, pp. 151-218.

20. Thomas-Olalde, Oscar und Velho, Astrid (2011): Othering and its Effects - Exploring the Concept. In: Lang, Peter (2011): Writing Postcolonial Histories of Intercultural Education. Available online, at: https://www.peterlang.com/view/9783653020045/9783653020045.00004.xml (Last visit: 29.04.2022).